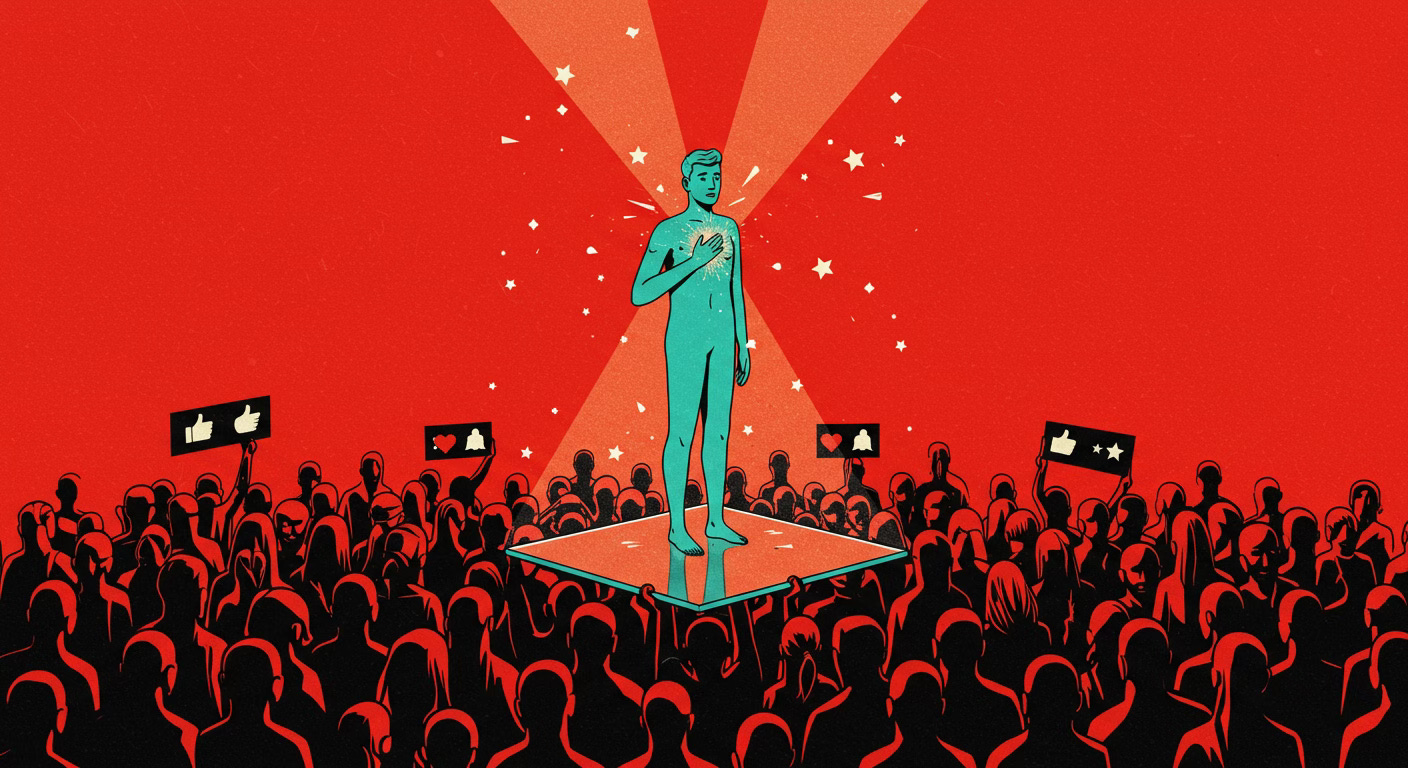

Human beings are natural evaluators. We assess ourselves constantly—measuring our strengths, validating our talents, and clinging to skills we believe distinguish us. However, in this continual process of self-estimation, a quiet trap lies in wait: the tendency to overestimate what we already possess, and to simultaneously undervalue what we lack. This estimation trap, though seemingly benign, becomes a silent saboteur, particularly in fast-evolving environments where the demands of the external world change more rapidly than we can comfortably adjust.

The trap is forged from a blend of psychological anchoring, emotional attachment to one’s identity, and a subtle fear of reinvention. We are often so invested in what we have always believed to be our core strengths—be it intellect, wit, charm, or technical expertise—that we blind ourselves to the rising currency of other traits or competencies. This creates a self-confirming bias, where we selectively see the world as affirming our worth, even when the rules of the game have changed.

Take for instance the realm of seduction in the digital age. Someone whose strengths lie in humor, intellectual depth, or emotional intelligence may find themselves frustrated by the mechanics of modern dating apps, where physical attractiveness is the primary filter. In such contexts, inner qualities often become invisible unless preceded by compelling aesthetics. The intellectually confident person might continue relying solely on what worked in face-to-face interactions of the past, ignoring the visual-first design of contemporary dating platforms. Their overestimation of their "deeper" qualities and simultaneous underestimation of surface-level attraction places them at odds with the prevailing system.

A similar dynamic unfolds in the professional world. Graduates in the humanities, armed with analytical thought and critical reasoning, may assume these timeless skills will be self-evidently valuable. Yet, as the market increasingly rewards fluency in data science, machine learning, and automation, those who fail to recalibrate their trajectory risk being sidelined. Their loyalty to the prestige or depth of their existing expertise, while emotionally understandable, becomes a liability when the world's attention shifts elsewhere. The estimation trap here masks itself as pride, or even moral resistance to trends perceived as shallow or overly commercial, but the outcome is the same: stagnation.

As psychologist Daniel Kahneman famously observed, "What you see is all there is." We tend to lean disproportionately on what we already know and overlook that which is outside our current field of competence. This can be especially perilous when success or relevance depends on the very qualities we haven’t yet developed. In essence, we trade adaptive learning for a comfortable illusion of sufficiency.

The estimation trap also thrives in the creative and artistic domains. An aspiring novelist might overemphasize their lyrical prose while dismissing the structural discipline of plot development or reader engagement. They believe in their voice, their originality—but readers respond to narrative clarity or emotional accessibility, not merely to verbal elegance. The mismatch between self-evaluation and audience expectation becomes a source of disillusionment.

This misalignment is rarely due to arrogance. More often, it’s rooted in an emotional attachment to our self-definition. What we are good at becomes who we are. Admitting that our strength may not be enough—or may even be irrelevant in a new context—feels like betraying the self. We fear becoming opportunistic or inauthentic. But identity must evolve. The wisest recalibrations are not betrayals but adaptations; they refine rather than replace our essence.

Ironically, the skills or attributes we resist developing often take less time to acquire than we imagine. The person reluctant to improve physical presentation could, with modest effort, upgrade their wardrobe or grooming. The humanities graduate could complete a short bootcamp in Python or SQL and immediately expand their career prospects. But so long as the estimation trap holds, they see such efforts as distractions rather than strategic investments.

There is a profound humility in accepting that the world may not reward what we most treasure in ourselves. Yet, there is also freedom in that humility—a release from self-imposed blindness. The great Stoic philosopher Epictetus once said, “It is impossible for a man to learn what he thinks he already knows.” Only by suspending our faith in the sufficiency of our current strengths can we begin to see what is actually needed.

Social comparison often aggravates the estimation trap. If one sees others succeed with qualities or tools one has dismissed, cognitive dissonance arises. Rather than adjusting, people may double down, insisting that their value will be recognized in due time. This defensive posture only deepens the disconnection from evolving realities. As Charles Darwin noted, it is not the strongest who survive, nor the most intelligent, but those most responsive to change.

Escaping the estimation trap requires two moves: internal disillusionment and external curiosity. One must be willing to gently question the supremacy of one’s core attributes and turn outward with genuine interest in what is now working, what is now valued. This doesn’t mean abandoning oneself, but rather enriching the self with new dimensions that speak the language of the present.

Ultimately, the estimation trap is not just about professional stagnation or romantic frustrations. It’s about the broader existential challenge of reconciling who we think we are with what the world currently requires. If we insist on seeing the world through the lens of our cherished but aging strengths, we risk becoming invisible in the very arenas we wish to enter. But if we temper our confidence with curiosity, and our pride with adaptability, we turn the trap into a trampoline—from which a higher, wiser self can spring.