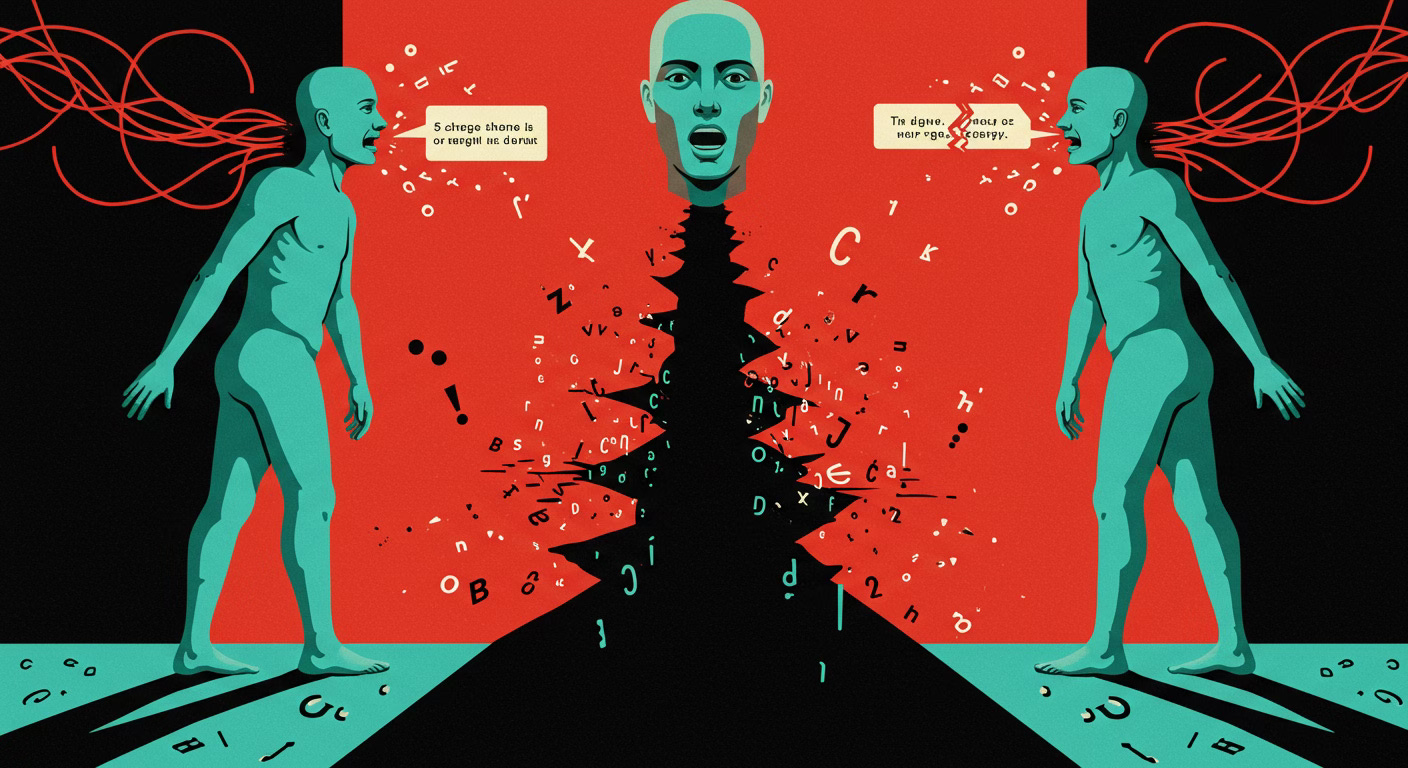

It is one of the profound ironies of the human condition: two individuals may share the same language, vocabulary, and grammar, and yet find themselves completely unable to engage in meaningful conversation. This paradox is becoming increasingly visible in our hyper-connected world, not because of linguistic barriers, but due to something far subtler and more insidious—dogmas. Dogmas, whether ideological, political, religious, or cultural, often act like invisible filters that warp perception and obstruct dialogue, even between those who ostensibly speak the same tongue.

Dogmas offer psychological safety. They function as pre-constructed belief systems that help individuals locate themselves in the chaos of existence. In this sense, they serve a valuable purpose. However, over time, they harden into intellectual fortresses, designed less to explore and more to defend. When someone who subscribes to a dogma enters into a conversation, their aim is not to listen, but to protect. Language becomes weaponized—not a bridge, but a barricade.

This defensive stance becomes particularly problematic in societies where pluralism is the norm. In such contexts, the multiplicity of viewpoints should naturally foster dialogue. And yet, ideological enclaves thrive. People gravitate toward echo chambers where their beliefs are reaffirmed, not questioned. Dialogue with the “other side” becomes at best a debate to be won, and at worst, an existential threat to be silenced. The art of true conversation—of mutual discovery and collaborative understanding—becomes a casualty.

Dogmas are generally imported or inherited. Few people actually construct their belief systems from scratch. Instead, they absorb them from religion, media, culture, family, or educational institutions. These beliefs are rarely re-examined, let alone redefined. Because they are externally acquired and often deeply internalized, they are fragile. And because they are fragile, they must be defended. The result is a perpetual cycle of avoidance or hostility in the face of difference.

By contrast, ideas forged through personal reflection, trial, error, and life experience tend to be more resilient. A person who has arrived at a worldview through inner thought rather than outer imposition is less likely to feel threatened by alternative perspectives. These ideas, born from lived experience, invite scrutiny. Such a person often finds joy in dialogue—not because they wish to dominate, but because they are still learning. They are secure enough to open their ideas to the air, knowing that what is solid will survive, and what is flawed will evolve.

Consider two political activists on opposite sides of a contentious debate. Both speak perfect English. But one is driven by inherited dogma, passed down through party lines, media soundbites, and ideological orthodoxy. The other, while still committed to a cause, has formed their views through experience: volunteering, reading widely, failing, recalibrating. The conversation between the two quickly breaks down. Not because of disagreement, but because one cannot engage without protecting a fragile identity built on second-hand certainties.

The difference is not merely intellectual, but emotional. Dogmas wrap themselves around a person’s sense of self. To challenge a dogma, then, is to challenge the very integrity of a person’s being. This is why, even in seemingly casual conversations, responses can be disproportionately aggressive or dismissive. The stakes feel existential. As Dostoevsky once remarked, “Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him.” And dogmas are the great inhibitors of such understanding.

In families, this dynamic can be especially toxic. Parents and children, or siblings, may find themselves incapable of talking politics, religion, or morality, even though they share a common language and lineage. The fear is not of misunderstanding the words, but of piercing the ideological bubble that maintains familial harmony. This results in ritualistic conversations—safe, predictable, and ultimately void of meaning.

In workplaces, similar tensions arise. A company may proudly declare its support for diversity, but in practice, ideological diversity is often discouraged. Employees learn to self-censor, to avoid offending colleagues who might be operating under different dogmatic systems. The workplace becomes a stage for performative agreement, rather than a laboratory for genuine collaboration and innovation.

Social media platforms further exacerbate this phenomenon. Algorithms reward polarization. As users are fed content aligned with their existing views, their dogmas are continually reinforced, not challenged. The ability to empathize, to engage across ideological divides, atrophies. And when they do encounter a dissenting view, it is often in a decontextualized, caricatured form—easy to dismiss, impossible to understand.

Philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti once said, “Tradition becomes our security, and when the mind is secure it is in decay.” This insight captures the psychological trap of dogma. What begins as an intellectual comfort becomes a prison. And when enough people live in such prisons, the very concept of dialogue collapses. Conversation becomes transactional or tribal. Truth becomes secondary to loyalty. Language is preserved, but meaning is lost.

However, there are models of hope. In certain educational settings, the Socratic method is still alive—a process where students are encouraged not only to question others but to question themselves. In such spaces, dogmas are temporarily suspended. Ideas are not sacred, but provisional. The goal is not victory, but clarity. And it is in these fleeting moments that we are reminded of the power of dialogue.

The real tragedy is not merely that dogmas prevent understanding, but that they prevent evolution. Ideas are meant to grow, to mature. Dialogue is their fertilizer. When people retreat into ideological bunkers, they starve their own potential. They become stranded in the safety of inherited thoughts, while the world around them continues to change.

To overcome this, we must learn to detach identity from ideology. We must teach ourselves—and the next generation—that to be wrong is not to be weak, and to change one’s mind is not to betray one’s tribe. As Rumi said, “Try not to resist the changes that come your way. Instead, let life live through you.”

In the end, perhaps the solution lies in humility. To approach each conversation not as a warrior, but as a learner. To be willing to ask not only “what do you believe?” but “how did you come to believe it?” When language is infused with such openness, when dogmas are held lightly, and when minds are lit by the fire of curiosity rather than the cold steel of certainty, then we may yet find our way back to each other—not just speaking, but truly talking.